Madison’s downtown has seen a boom in residential and mixed-use development, and the city’s 2012 Downtown Plan aims to guide and balance density, vibrant and walkable streets and public spaces, and historic preservation. A number of persistent challenges remain, however, particularly the downtown’s thin connection to Lake Monona, transportation hotspots, and a need for more public parks. The Madison Design Professionals Workgroup, a team of local architects, designers, planners, and real estate professionals dedicated to improving downtown, proposed putting traffic on a heavily traveled downtown portion of US Highway 151 in a tunnel and building new public park land on top, a project called “decking.”

Is this idea the best way to solve these problems? What would the spillover effects be, both positive and negative?

1000 Friends of Wisconsin has analyzed this idea from the point of view of public space, neighborhood connectivity, transportation, and environmental factors. This week, we share some of that analysis.

Today, we will introduce the basics of the proposal. On Wednesday, we will address the benefits to the neighborhoods, the downtown, and the city as a whole; on Thursday, we will look at the problems and issues this project would face and where more research is needed.

What is Decking, and what does it look like?

Interstate highways didn’t just connect cities; in many cases, they cut them into pieces. Originally envisioned as a way of connecting cities and regions across the country with high-speed, high-capacity roadways, interstate highways came to dominate the urban core as well. Traffic engineers and state and federal agencies tried to solve some of the major problems created by freeways—namely, congestion and pollution—by doubling down on the same ideas that created the problems in the first place. Freeways were constructed and widened straight through downtowns and urban (often minority) neighborhoods, destroying community connections, historic districts, and green space. In an unfortunate and (in hindsight) thoroughly predictable turn of events, American cities got few of the promised benefits of additional freeway capacity and a heavy dose of its side effects.

Milwaukee’s Marquette Interchange, originally built in 1968 and rebuilt in 2008, resulted in the symbolic and literal destruction of the core of the city’s old transportation infrastructure, Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company’s Transport Building.

Another Milwaukee freeway, Interstate 43, destroyed Bronzeville, one of the most vibrant early to mid-twentieth-century African-American neighborhoods in the Midwest and a hotbed of jazz and entertainment.

Madison avoided plans to build an elevated expressway through the heart of its downtown, but the construction of John Nolen Drive in 1967 separated downtown from the Lake Monona waterfront and continues to bedevil proposals to improve public access to the lake.

Some cities with urban freeways have figured out something very important—that the air above every urban freeway is some of the best land they have. They can’t replace what was destroyed when the freeways were built, but they can reclaim the space above them and improve surrounding neighborhoods and communities as a whole.

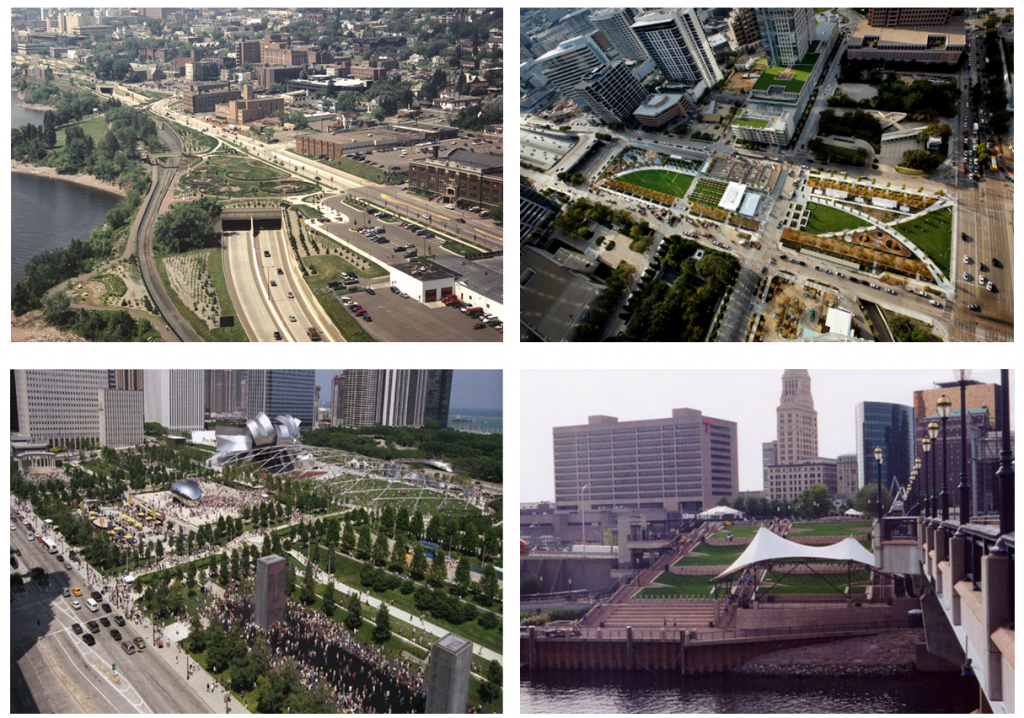

Seattle’s Freeway Park, built in the late 1970s, is acknowledged as one of the earliest decking projects. An elaborately terraced platform over Interstate 5 in Downtown Seattle, the park was a costly investment that nonetheless inspired a trend.

Many other cities of all sizes and across the country have followed suit, including Duluth, MN, Dallas, TX, Hartford, CT, and Chicago. None of these parks are exactly alike, but they all involved investment in infrastructure to create new public space above a freeway.

What’s Being Proposed in Madison?

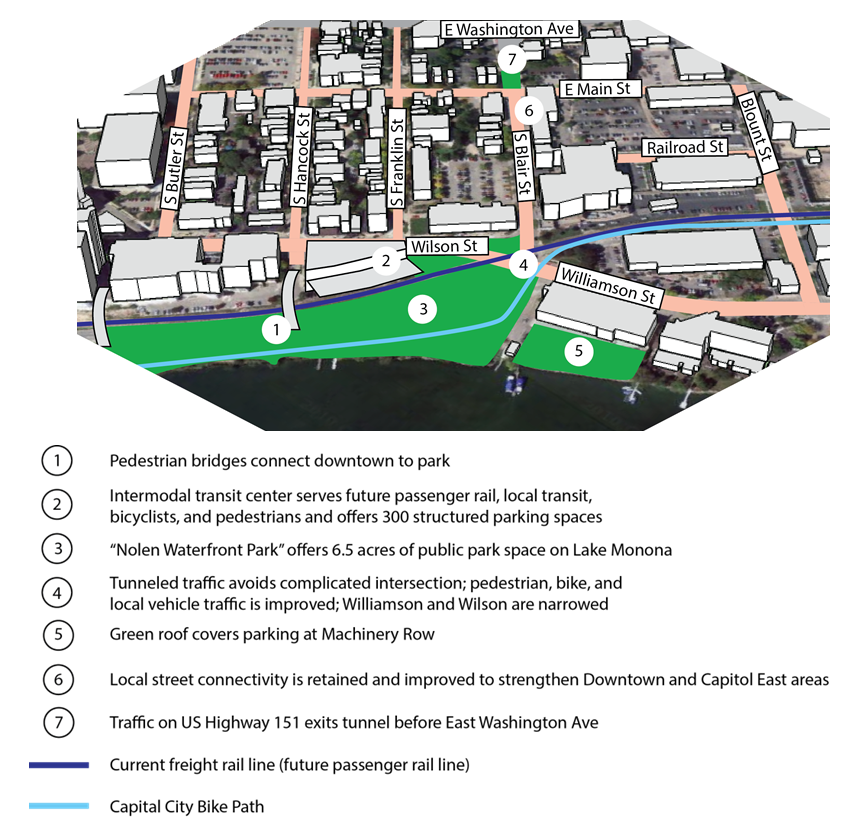

To reconnect Downtown Madison to Lake Monona and solve the transportation problem of John Nolen Drive and the gateway intersection, the Design Professionals have proposed sending inbound and outbound traffic on John Nolen Drive underground from just east of the Monona Terrace convention center to somewhere along South Blair Street. Where once was open air above a highway, they propose expanding the thin green strip known as Law Park by more than six acres. The surface streets, Williamson, Wilson, Main, Railroad, and a leg of South Blair Street, would stay connected as local roads to help distribute neighborhood traffic and move pedestrians and bicyclists around more easily.

The plans also call for building a transit center on the southeast corner of Wilson and Hancock to take advantage of potential passenger rail using the tracks that bisect the project area. This transit center would also have around 300 underground parking spots.

Below is a more detailed illustration of the important features of the proposal.

Ultimately, what would this space look like and feel like from eye level?

Here’s what you see currently on a sunny day at the intersection of John Nolen Drive, Wilson Street, and Williamson Street (left), and the view from a successful decking project in Dallas (right):

Here’s a waterfront park in Washington, DC with a downward slope similar to what could be built to connect Madison’s downtown to Lake Monona:

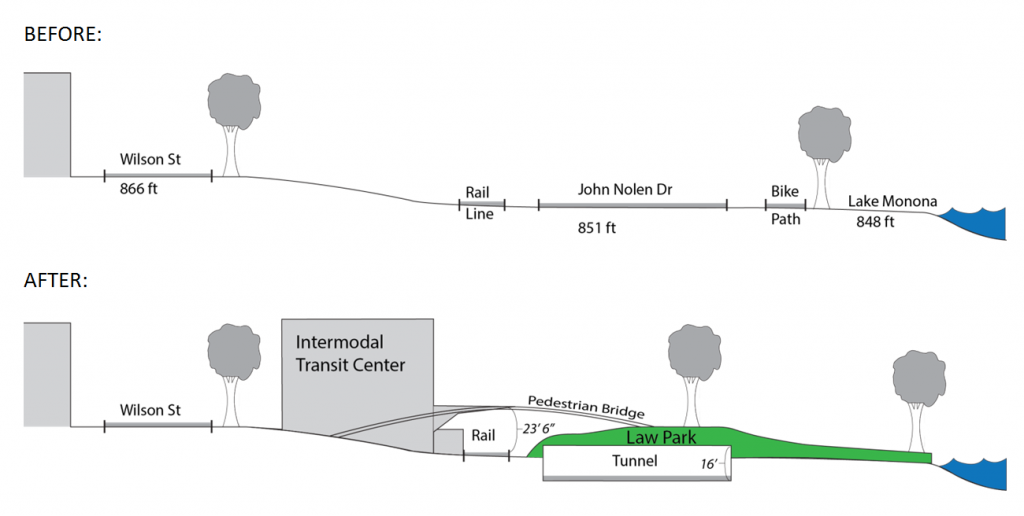

Here’s what a cross-section of the project area looks like today versus under the decking proposal.

One of the most important things to see here is the pedestrian bridges, which take advantage of the natural slope down to the lake and create new access points for pedestrians and people with disabilities to get to the lakefront park.

It’s an interesting idea, to be sure, but what would it do for the neighborhood and for the city as a whole? What are the costs and potential downsides?

We will be exploring this issue in the coming week. Stay tuned for more.

-Matt Covert is the Green Downtown Program Manager for 1000 Friends of Wisconsin

Read his paper about decking over John Nolen Drive in Madison.