As promised, 1000 Friends is sharing some more in-depth analysis of the proposal to bury John Nolen Drive and Blair Street in a tunnel, build a park on the surface, and reconnect the surface street grid. Today, we tackle some of the primary benefits of this project from the transportation, environmental, and civic points of view.

Benefits to the Transportation System

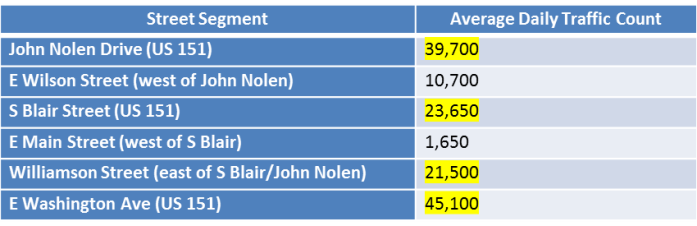

It is no secret that as a federal highway and the main route for through-traffic in Downtown Madison, Blair Street and John Nolen Drive form a formidable barrier to movement of people between downtown and the near east side. What happens if we take almost 24,000 cars a day (the volume on South Blair Street) and put them underground?

By tunneling that commuter traffic, congestion and volume decrease on surface streets (including a rebuilt, downsized Blair Street above ground). This does a couple of important things:

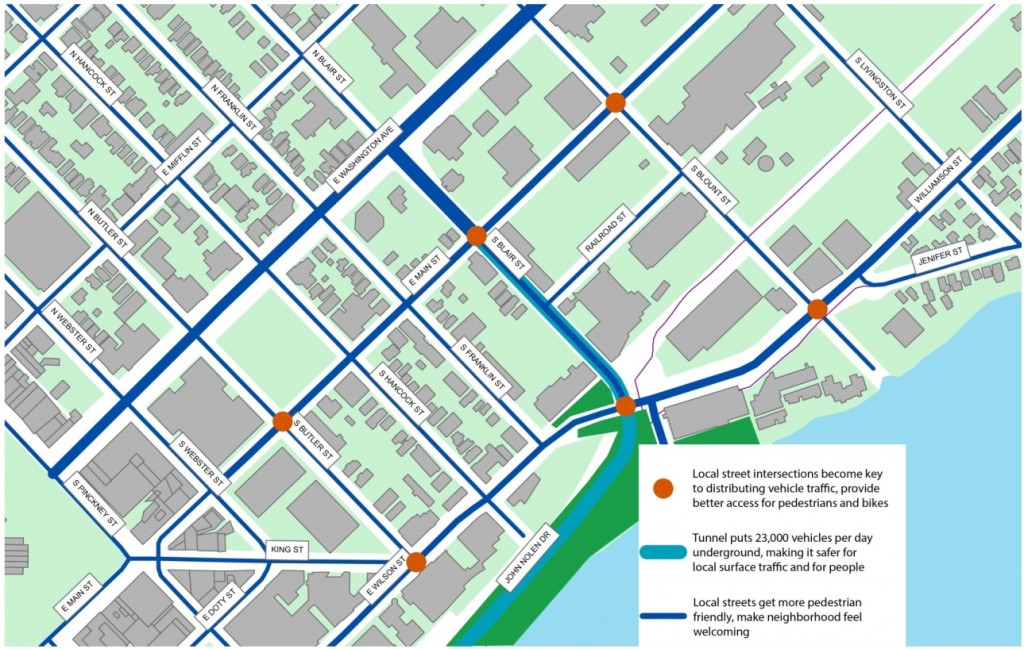

- It allows the street grid, which is vital to distributing local traffic, to thrive. Streets that used to be designed for highway and commuter traffic, like Wilson Street and Williamson Street, can be narrowed and redesigned, with more space given to pedestrians and quality public spaces;

- Second, it creates opportunities for a local commercial district to develop along Main and Williamson. Establishing an employment district in the Capitol East area has been a priority for the city; wouldn’t it be great if this district was actually tied to Downtown and residential areas on the near east side with high-quality local roads and other transportation infrastructure?

Above, a map displaying the primary transportation fixes this project would provide.

Benefits to the Urban Environment

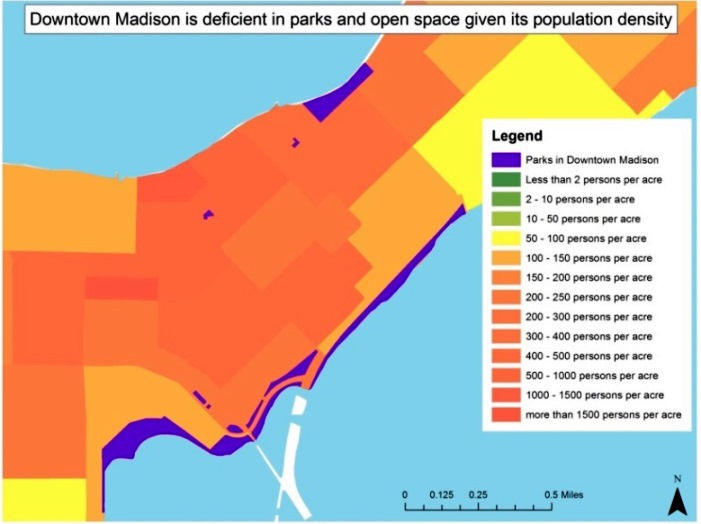

Downtown Madison is very dense (over 23,000 people live in an area less than a square mile in size). As you can see in the map below, only 3 small parks (a total of 45 acres) serve this area, and Law Park, next to John Nolen Drive, is a skinny green strip next to a federal highway that is daunting to reach on foot.

Creating Nolen Waterfront Park on top of a tunneled John Nolen Drive would increase the park acreage in Downtown Madison by 13 percent. Because parks and urban green space have substantial quality of life and environmental benefits, downtown residents and visitors stand to benefit substantially.

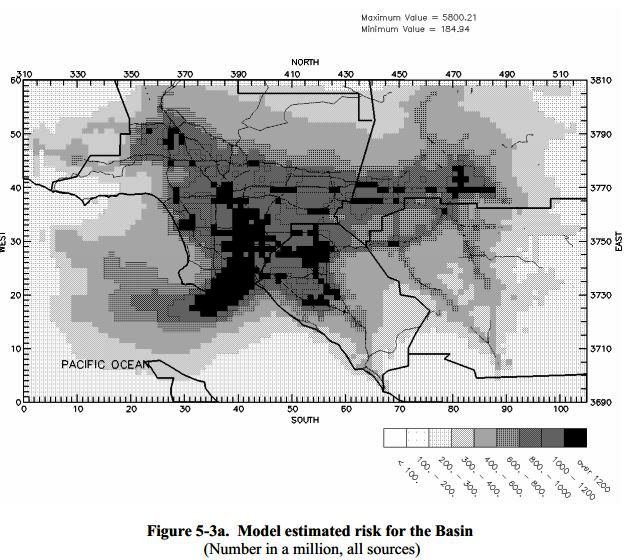

One of the main benefits to the urban environment is undoubtedly air quality. Urban freeways pose air quality hazards for everyone, especially residents. A series of landmark studies in Los Angeles discovered tremendous air pollutants and health hazards next to the city’s port and along its freeways.

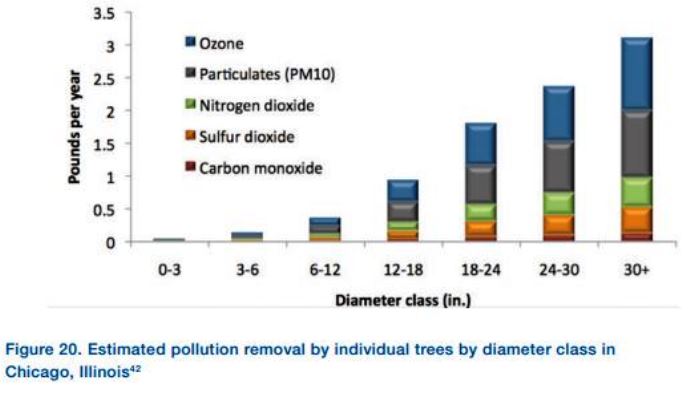

Parks, and more specifically trees, remove substantial amounts of pollutants. The following chart shows the weight of pollutants removed from the air per year by type of particle and by diameter of the tree. Putting large volumes of highway traffic underground, therefore, already reduces the spread of air pollution, and when combined with a surface park and an addition to the urban canopy, even more pollutants are removed from the environment.

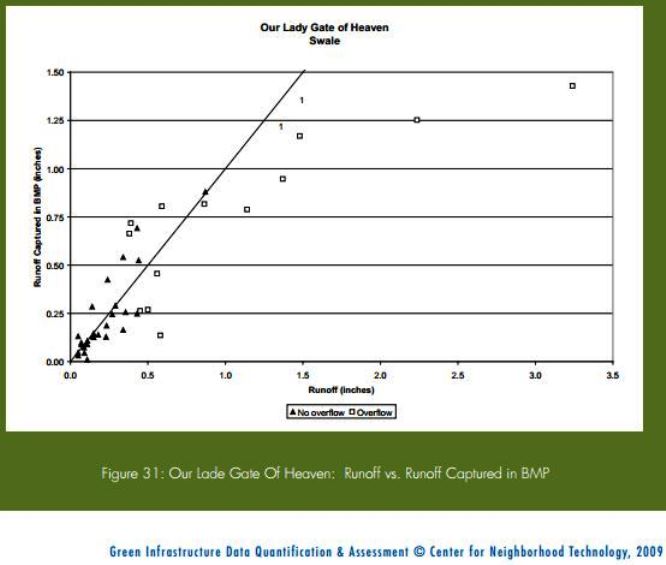

This project also has the potential to increase water quality in Madison’s lakes. Urban runoff is a major concern in Madison and other surface water-adjacent cities. A particularly effective way of dealing with that runoff is building rain gardens, bioswales, or other types of so-called “green infrastructure.” In fact, another Downtown Madison park, Brittingham Park, is home to substantial rain gardens that have improved the water quality in Monona Bay.

These features work because water otherwise destined to run into storm sewers and straight into the lakes is captured in low ground that often features an abundance of native shoreline plants that are very effective at holding water in place and allowing it to slowly absorb into the ground, leaving behind the particulates, gravel, sand, salt, and chemicals that rainwater sweeps off urban surfaces. However, they also need space, and currently, Law Park is too narrow to filter urban runoff adequately. A major park expansion would both eliminate a paved surface—the roadway—that contributes to water pollution and create an opportunity to treat runoff in a sustainable, aesthetically pleasing way.

This study, from Seattle, shows that rain gardens and other green infrastructure often capture 100% of the water from even major storm events.

Benefits of the Project as a Civic Objective

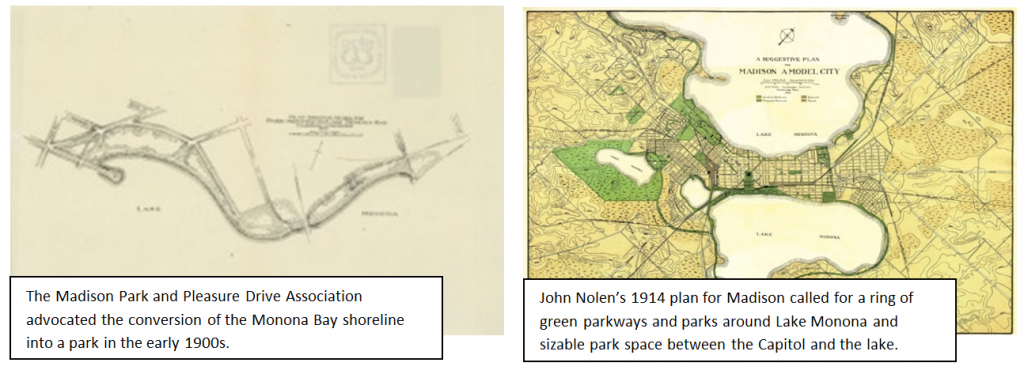

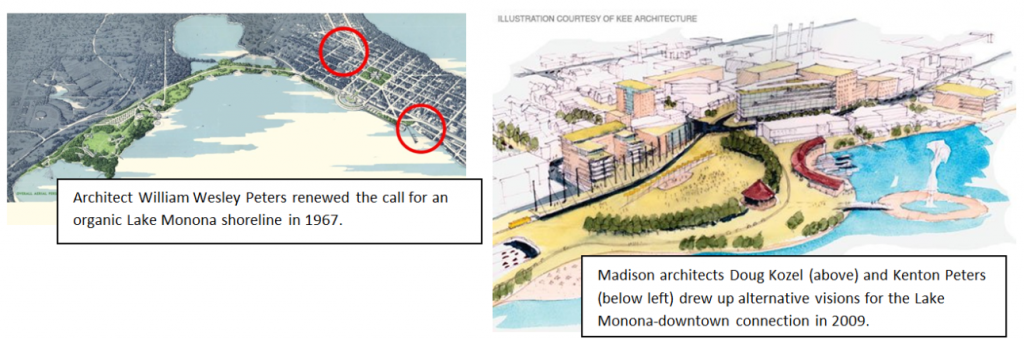

Over the decades, the Lake Monona shoreline has been the subject of many bold visions, both large-scale and small-scale in nature. Parks are an important civic objective in part because they provide a public space where anyone, from any class, ethnic group, and background can experience nature in an urban environment. They are an egalitarian concept popularized in the late 19th century by urban reformers, who saw public investment in urban green space as a social necessity.

Beginning with the Park and Pleasure Drive Association in the early 1900s and reaching an apex in John Nolen’s city plan, Madisonians have long desired a strong connection between the downtown and the Lake Monona waterfront. What we got instead was a high-speed urban highway separating downtown from the lake. A project like the one proposed here is merely the latest evolution of a very old idea.

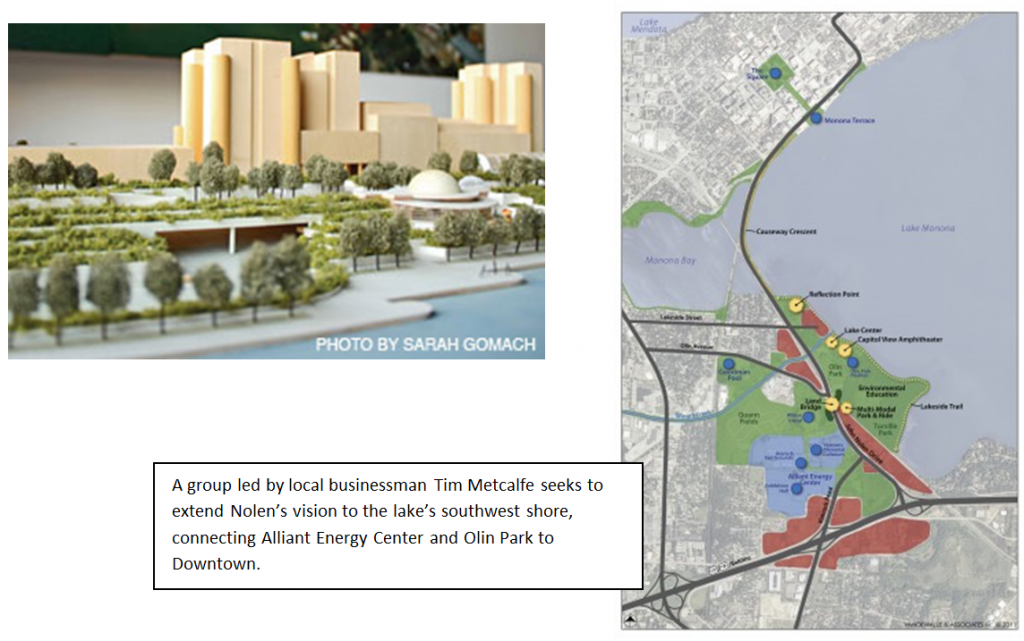

Below, are some of the major steps in the evolution of planning the Lake Monona waterfront.

We will take a look at some of the potential downsides and negative consequences of this proposal early next week. Stay tuned!

-Matt Covert is the Green Downtown Program Manager for 1000 Friends of Wisconsin

Read his paper about decking over John Nolen Drive in Madison.