Roads themselves are often overlooked in our urban land use pattern, even though streets and sidewalks can make up almost 80% of the public space in cities. In fact, in downtown Milwaukee, nearly 40% of the total land is devoted to road infrastructure. Most of these streets are necessary to create a complete transportation network. However, large urban freeways, which dominate the landscape, have caused more harm than good.

To many, these freeways have always existed, serving as a vital link between downtown and the suburbs. There is no memory of the neighborhoods destroyed, the urban fabric torn apart. The true societal cost of these freeway projects has become muddled. To understand the consequences behind highway construction, we need to review what we lost in the trade-off.

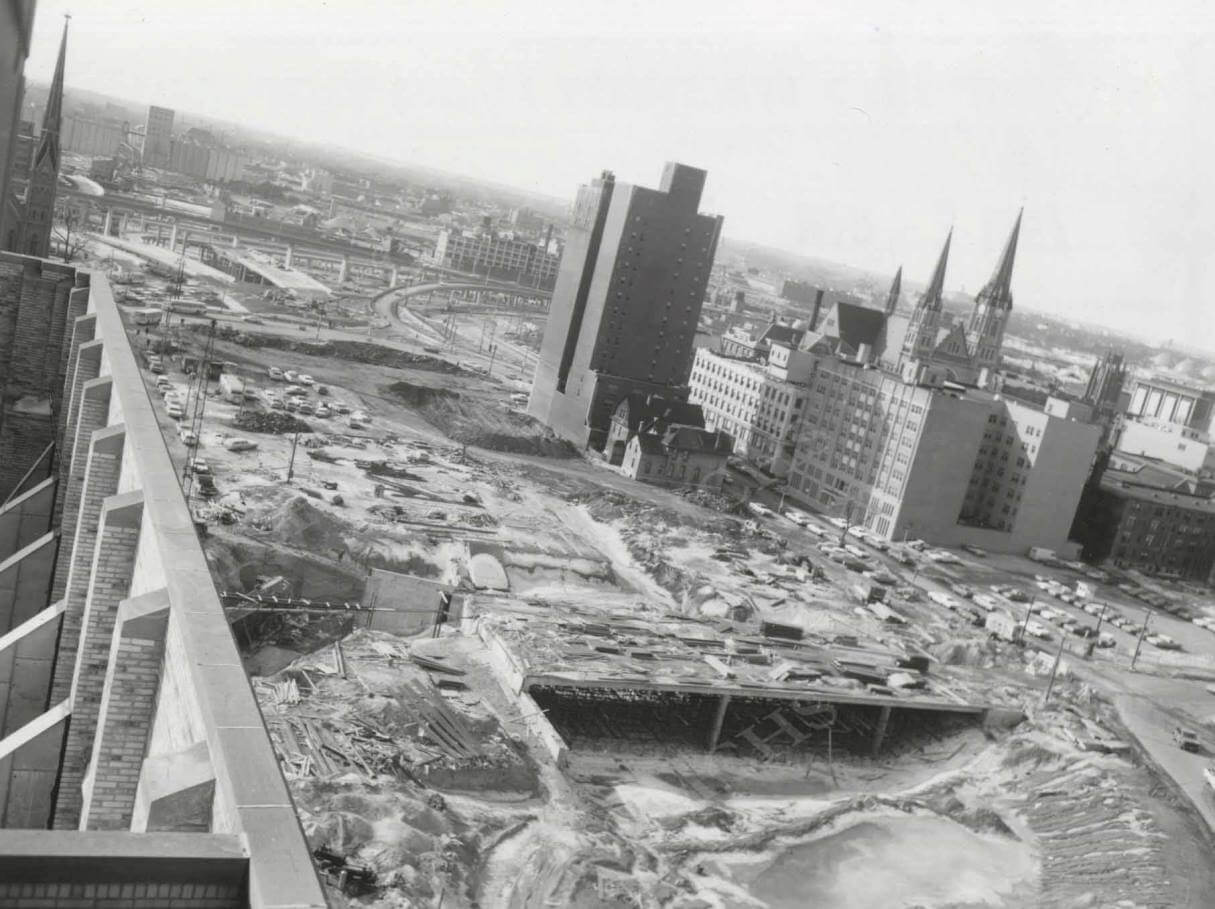

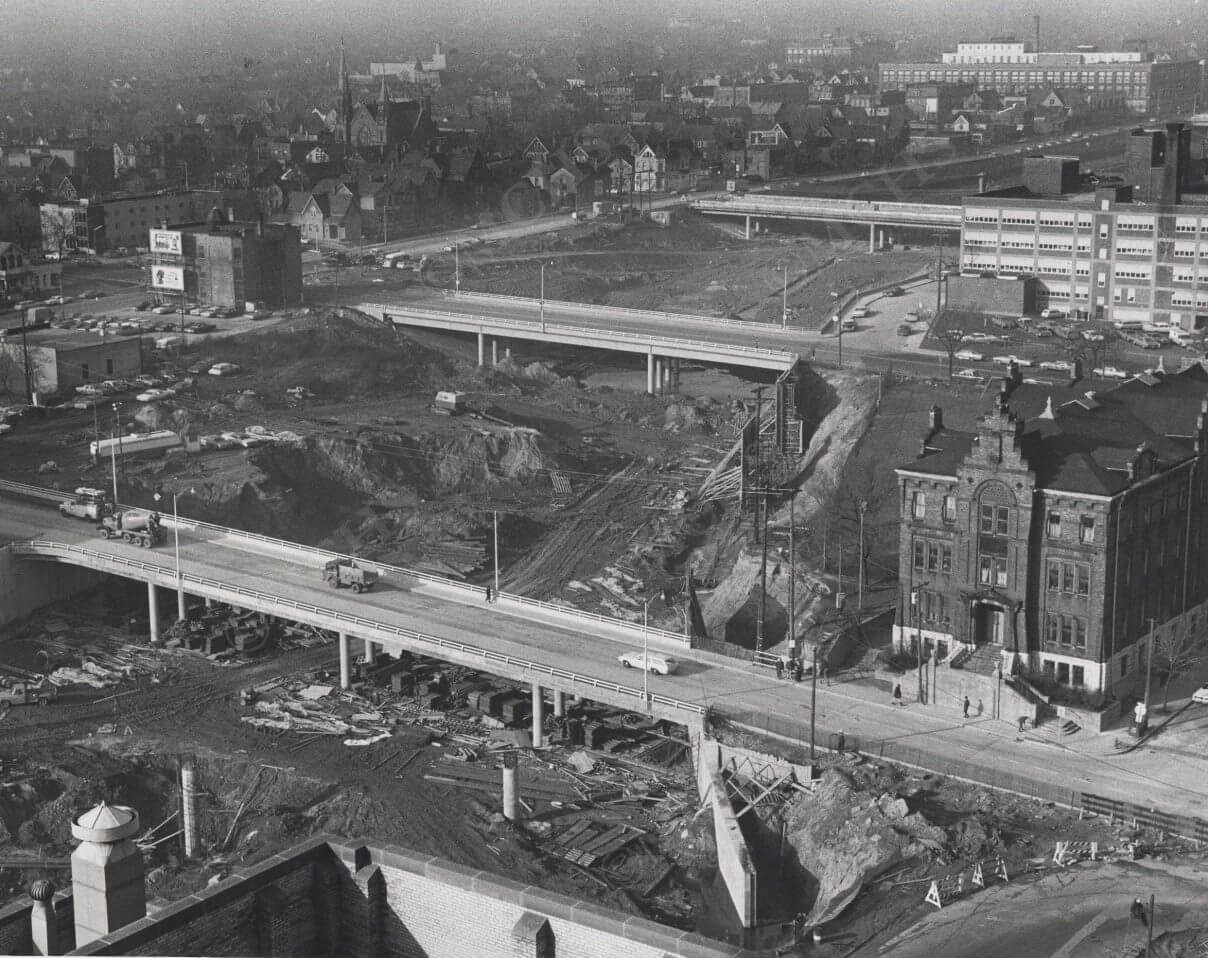

Starting in the 1950’s, engineers and urban planners began looking at downtown freeways as a vital resource to maintain the health of cities, and by 1956, over 90% of highway costs were covered by the federal government. Unlike European cities which built highways on the perimeter of their communities, US policy looked to facilitate movement to the core of downtown from the suburbs. Construction began in the early 1960’s. To build these downtown freeways, Milwaukee planners used eminent domain to seize more than 6,000 homes and relocated 20,000 residents in the name of urban renewal.

In Milwaukee, much of the blow was dealt to the vibrant, primarily African-American neighborhood of Bronzeville. At this point, African Americans in Milwaukee were largely denied suburban home loans by the federal government through redlining. Restrictive covenants also ensured that homeowners could not sell their homes to minorities. They were also denied careers and opportunities that would allow them to buy new homes, especially as job centers shifted to suburban communities. These restrictions left African Americans in small, urban neighborhoods that were labeled by city planners as blighted and in need of redevelopment. Prime targets for urban freeways. The destruction included successful African-American businesses, places of worship, and the growing economic, social, and political prosperity of the community.

The impact was devastating, displacing residents and businesses and replacing them with a highway system that increased vehicle emissions and noise while isolating the remaining neighborhoods from the larger city. The impacts are still present today as minority neighborhoods are exposed to, at times, 75% more vehicle emissions than predominately white neighborhoods. Residents of these neighborhoods also make up a disproportionate number of Milwaukee County’s pedestrian deaths.

These urban freeways were also a detriment to the larger city as well. Not only did they add expensive infrastructure to maintain, they also eroded Milwaukee’s budget by replacing tax-generating businesses and homes with non-taxable infrastructure. Nationwide, municipal budgets were hallowed out and cities were forced to reduce essential services. This furthered the lure of the suburbs at the expense of central cities in an insidious cycle. It also greatly hindered transit’s ability to compete with the automobile, leading to its decline and a justification to further invest in automobile-centric infrastructure.

All of this was done in the name of suburban commuters. Milwaukee remains one of the most racially and economically segregated cities in the country. The devastation caused by these highways continues to this day. Dr. Kirk Harris, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, puts it best when he says, “During our urban renewal period of the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s, the development of highways, consistent with public policies for housing development in the suburbs actually decimated Black and Brown communities. In fact, they would run through those communities and they would then create barriers in those communities, locking those communities in a further segregated experience. Highways have historically been a defining structure for what I would call inequality in America in our urban region.”

Downtown urban freeways, like those in Milwaukee, have been a social, fiscal, and environmental mistake. These project destroyed minority communities, increased greenhouse gas emissions, and strained local and state budgets, all in the name of reducing suburban commute times. This mindset is still present, as Wisconsin continues to expand its urban freeway network. Instead of perpetuating an inequitable transportation system, we should reinvest in quality public transit and active transportation infrastructure to start correcting all the damage that has been done.

Check out our final post exploring an urban freeway project in Madison that was proposed but never developed which helped make Madison one of America’s most livable places.

This is the penultimate post in a series highlighting the relationship between land use and transportation – the Transportation Connection – below is a full list of articles in the series.

Part 1: The Connection between Transportation and Land Use

Part 2: Mandatory Parking Minimums

Part 3: Minimum Lot Sizes

Part 4: Local Ordinances (Street Widths)

Part 5: Highways as Land Use