In our series on how to measure and interpret the sustainability and livability of our communities, we continue today on the theme of public space priorities. We know that walkability is important and that creating a better pedestrian environment improves the economy and vitality of our communities. Making choices for better walkability also goes hand in hand with creating better transit and bike accessibility. When we choose to build for and accommodate cars, however, achieving those other goals becomes more difficult.

Cars have added convenience to our lives in some ways, but are a burden in others. The great work done by Chicago-based Center for Neighborhood Technology demonstrates the impact of transportation costs on affordability and has been picked up by the federal government in affordability calculations. The average annual cost of owning a car, including gas, parking, insurance, and maintenance, is close to $9,000.

What those numbers don’t capture is the cost to the whole community of storing all those cars. Cars take up a great deal of space (a typical parking spot is nine feet by 18 feet, or 162 square feet), and an average car spends roughly 95 percent of its existence parked rather than moving, according to parking expert Donald Shoup. Because American communities were designed (or redesigned) around the automobile over the last sixty-plus years, they have been forced to find a place to put all those parked vehicles.

What those numbers don’t capture is the cost to the whole community of storing all those cars. Cars take up a great deal of space (a typical parking spot is nine feet by 18 feet, or 162 square feet), and an average car spends roughly 95 percent of its existence parked rather than moving, according to parking expert Donald Shoup. Because American communities were designed (or redesigned) around the automobile over the last sixty-plus years, they have been forced to find a place to put all those parked vehicles.

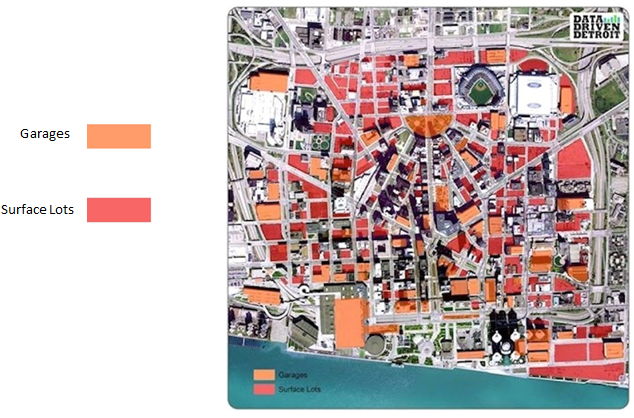

Solutions have included off-street parking minimums, subsidized parking for businesses, and the creation of multi-story parking garages. In the process, historic buildings and blighted areas were razed to build parking lots and ramps. Historic city centers and urban corridors, already dealing with tectonic shifts in economic conditions and difficulties of race and class, were pushed to further physical and financial ruin as whole blocks were taken off the tax rolls and added to the parking stall count. In Detroit (below), the unfortunate poster child for post-industrial decline, you can see the damage done to the urban fabric by all that parking:

Just as we can use the relative space allocated to pedestrians as an approximation of the health of our streets, like we did last week, we can also use the area occupied by parking lots and ramps in a city center as a percentage of the total land area. This kind of mapping can help us figure out how much land our communities have dedicated to parking cars instead of any other land use, and it can be a great communication tool as well: understanding how much parking your city has is difficult at ground level!

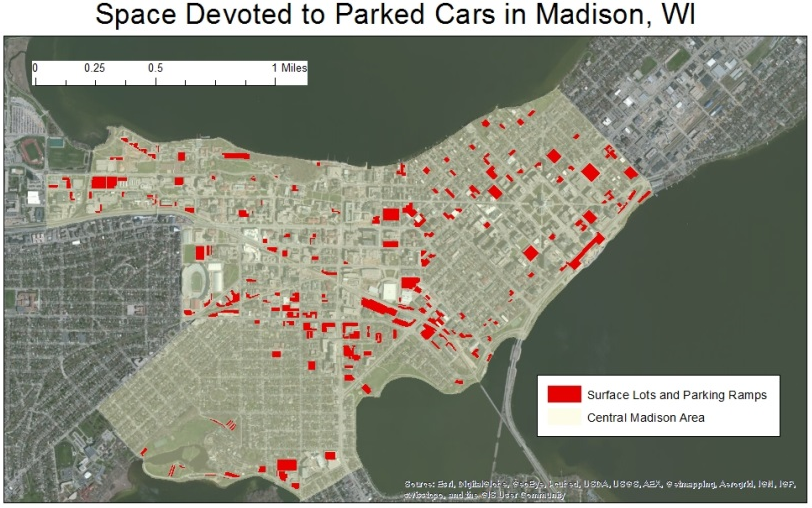

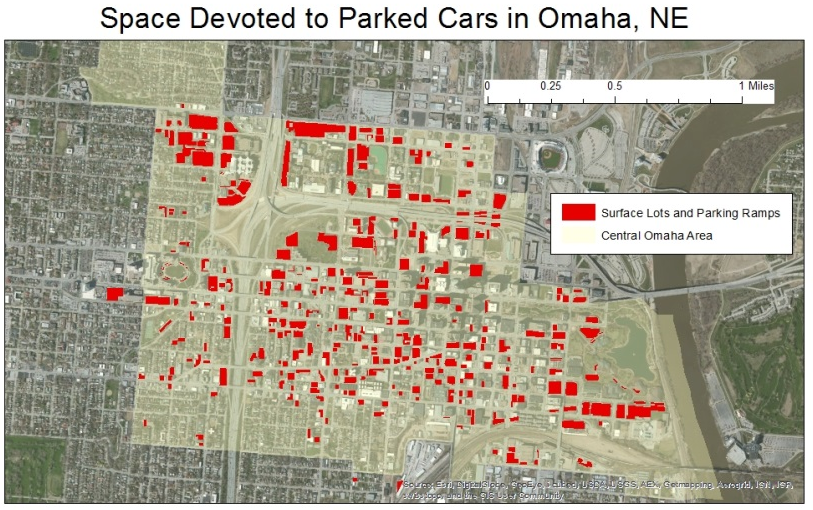

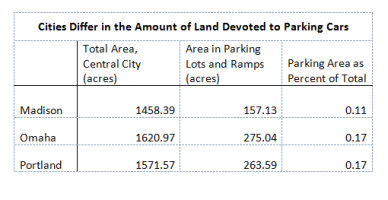

We have compared Madison, WI with two other communities: Omaha, Nebraska, another mid-size Midwestern city, and Portland, Oregon, a west coast metropolis famous for its walkable, transit-friendly downtown with which Madison is often compared. The parking lots were all drawn using aerial imagery, and the central city areas are an amalgamation of census tracts that contain at least some of the downtown area.

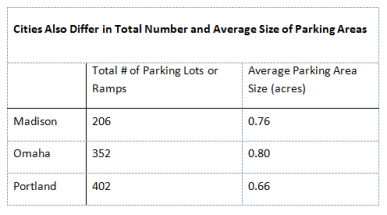

What we see from the maps and from the numbers is that in the greater downtown area, not including private driveways, back yards, or empty lots whose use as a parking lot may be incidental, all three cities have a greater number and spread of parking areas than might be expected. Spatially, Madison’s lots appear to be clustered more than the lots in Omaha and Portland, which are somewhat more evenly spread. Omaha and Portland devote the same percentage of land in the central city area to parking, which is surprising given Portland’s reputation. However, when we examine average lot size, we see that Omaha has the largest average lot size and Portland the smallest, with Madison in the middle. Portland, it seems, devotes a higher proportion of land than Madison to parking, but its lots are smaller on average, greater in number, and more dispersed than Madison’s.

What we see from the maps and from the numbers is that in the greater downtown area, not including private driveways, back yards, or empty lots whose use as a parking lot may be incidental, all three cities have a greater number and spread of parking areas than might be expected. Spatially, Madison’s lots appear to be clustered more than the lots in Omaha and Portland, which are somewhat more evenly spread. Omaha and Portland devote the same percentage of land in the central city area to parking, which is surprising given Portland’s reputation. However, when we examine average lot size, we see that Omaha has the largest average lot size and Portland the smallest, with Madison in the middle. Portland, it seems, devotes a higher proportion of land than Madison to parking, but its lots are smaller on average, greater in number, and more dispersed than Madison’s.

Next, we will examine pedestrian enhancements and infrastructure in various cities and whether those improvements are concentrated or dispersed. All these metrics can help give us a sense of whether a city is prioritizing public space for people and whether the pedestrian environment is conducive to vibrant, walkable streets than enhance community.