What is Walk Appeal?

One of the most crucial components of any healthy community is how walkable it is. Walkable communities are fitter, safer, and more socially cohesive, to say nothing of the benefits to businesses when customers can easily come on foot and by bicycle.

Often, we measure the walkability of a block, a street, a corridor, or a neighborhood by how dense it is with destinations and attractions. Physical distance to destinations is certainly an important part of walkability, but I argue that the experience of walking is equally important, if not more so. Have you ever gone out of your way to walk down a street that is interesting, safe, lively, and pedestrian-friendly, only to find yourself walking much further than you originally anticipated and enjoying the experience? Alternatively, have you ever stopped to think why we often drive from one big box store to another at suburban shopping centers, even though the stores themselves may only be 500 feet apart? I have, and I call this experience “Walk Appeal.”

The Tasks

With that hypothesis as the starting point, how do we gather information on how much Walk Appeal a street has? Sources of information that describe the walking environment are myriad and diverse, a mix of hard data (like building height, traffic counts, and sidewalk width) and individual perception (i.e., how safe do I feel walking here, and why?). Luckily, Madison has a wealth of bright, inquisitive college students at the University of Wisconsin. Earlier this summer, 1000 Friends partnered with a summer class in the school of Landscape Architecture to test data-gathering techniques.

Three students received the following tasks:

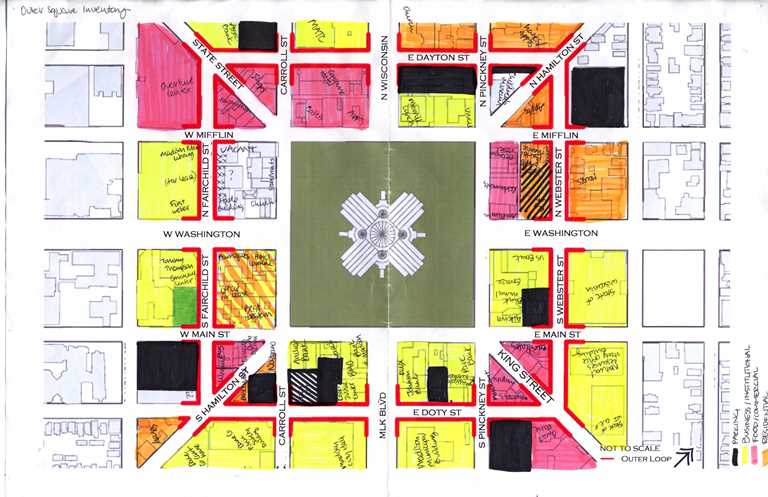

1. Go out walking on Downtown Madison’s Outer Loop (Dayton, Fairchild, Doty, and Webster streets around the state capitol building). Using a large printed (but unlabeled) map of downtown, categorize land uses in a way that makes sense to you.

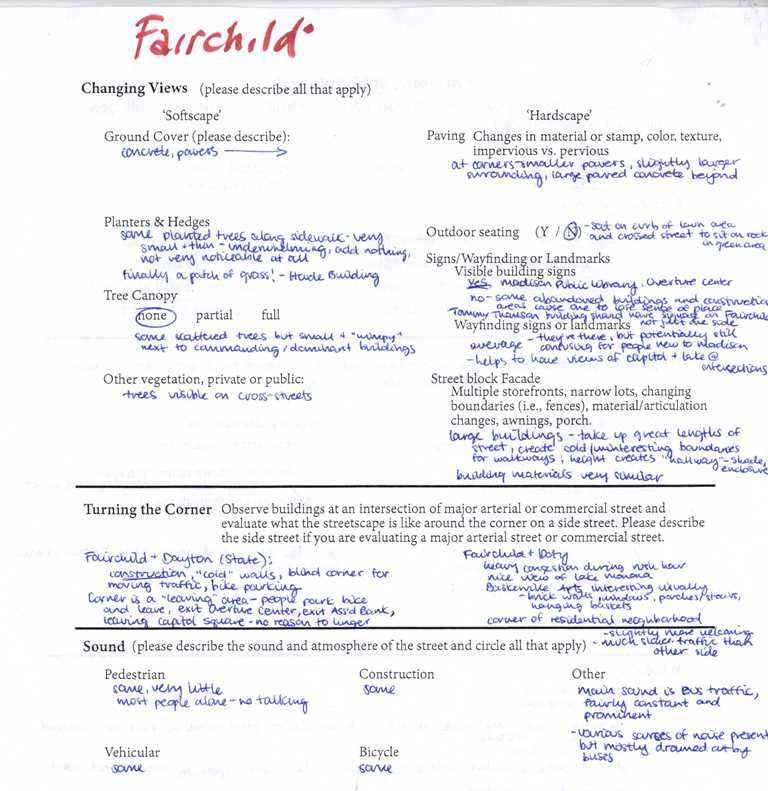

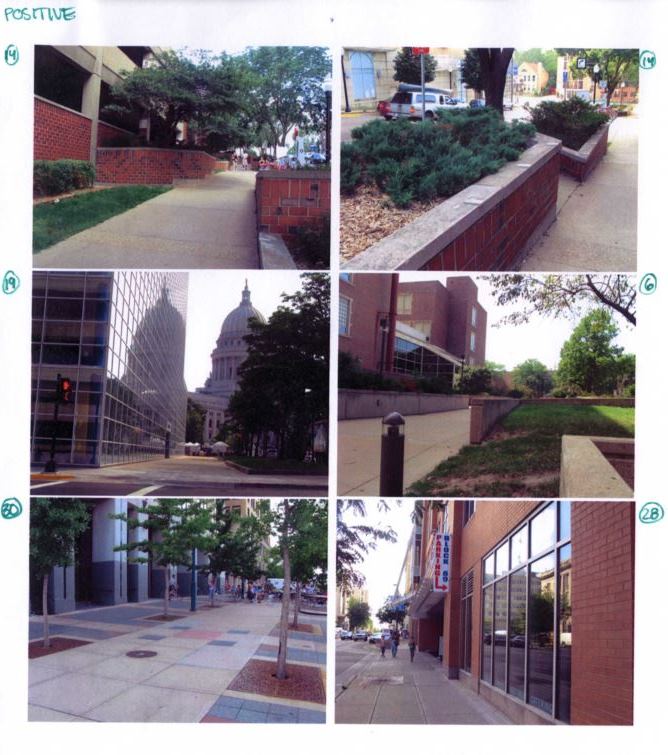

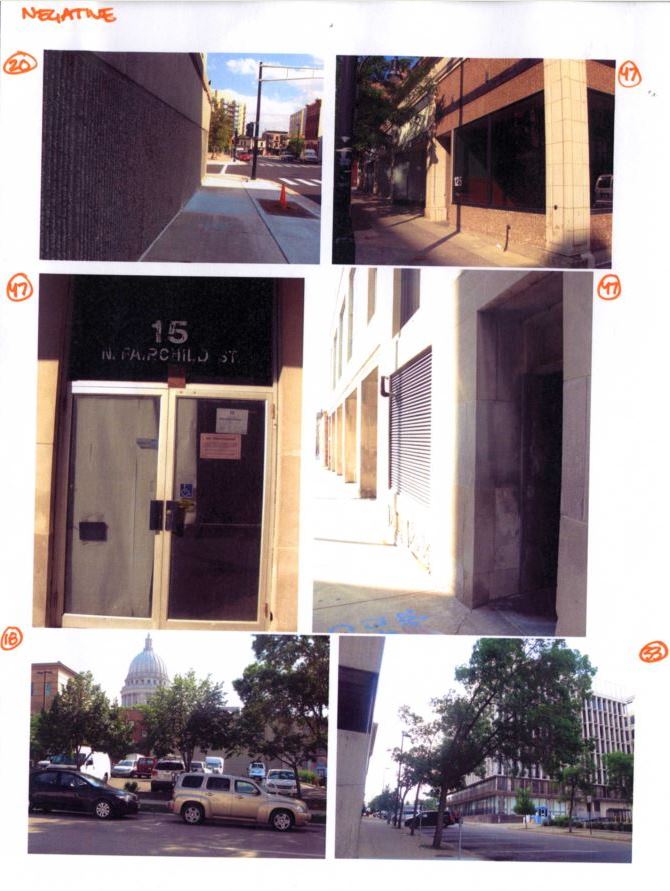

2. Take notes on what works and what doesn’t as far as the pedestrian experience is concerned. Take pictures of areas, situations, or spots that present particularly positive or negative experiences.

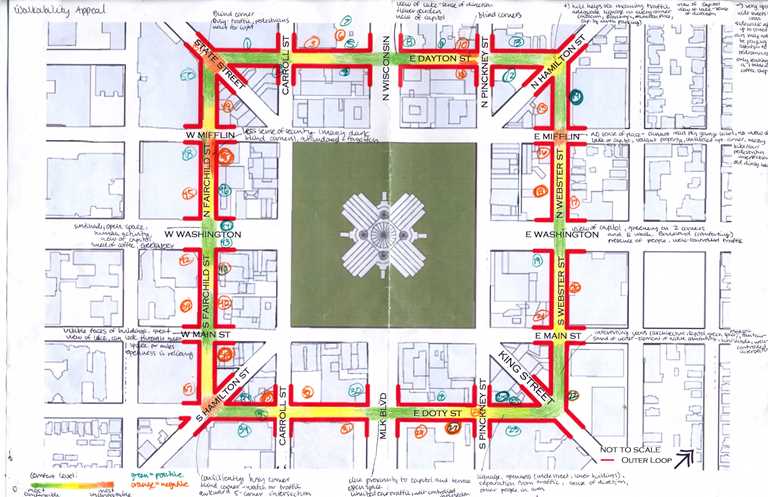

3. Using a walk appeal evaluation sheet, grade the streetscape as you go according to what you see and experience on the ground, at eye level, and overhead.

The Tools

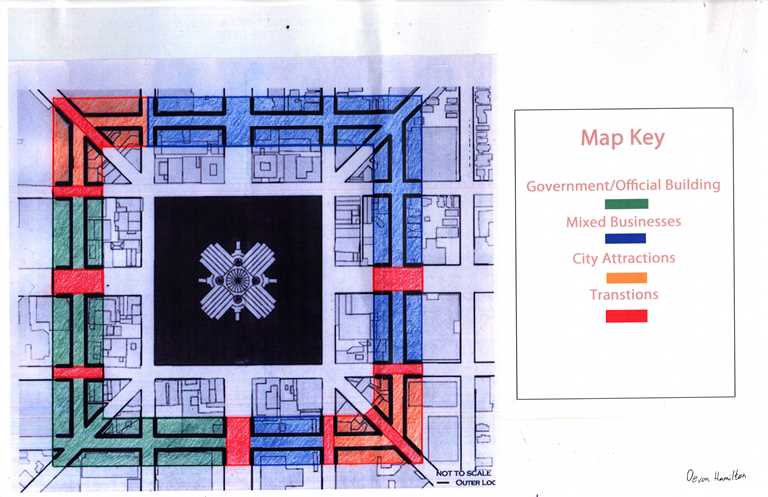

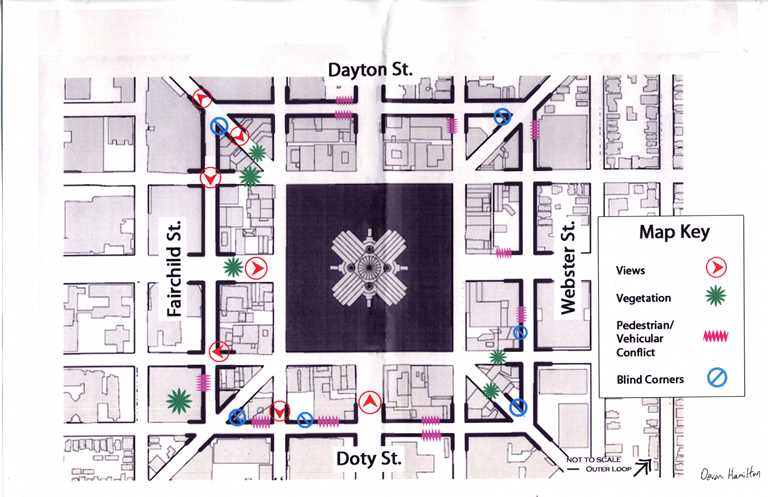

Students used a blank map of downtown that includes only streets and building footprint to shade the blocks of the Outer Loop according to land use and to grade their experience as pedestrians on each block. The finished maps are below:

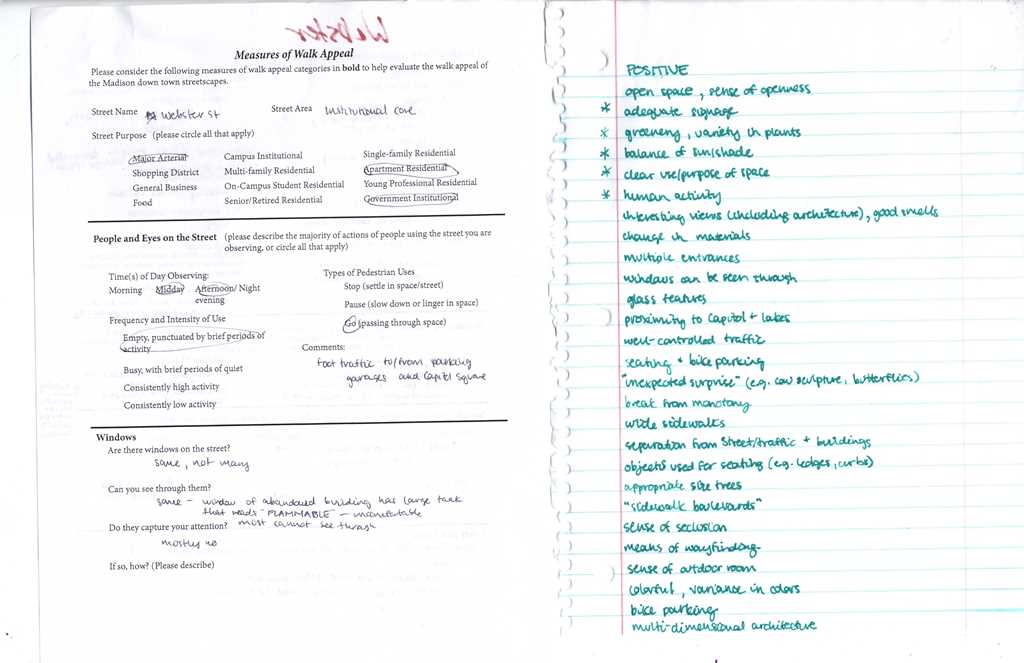

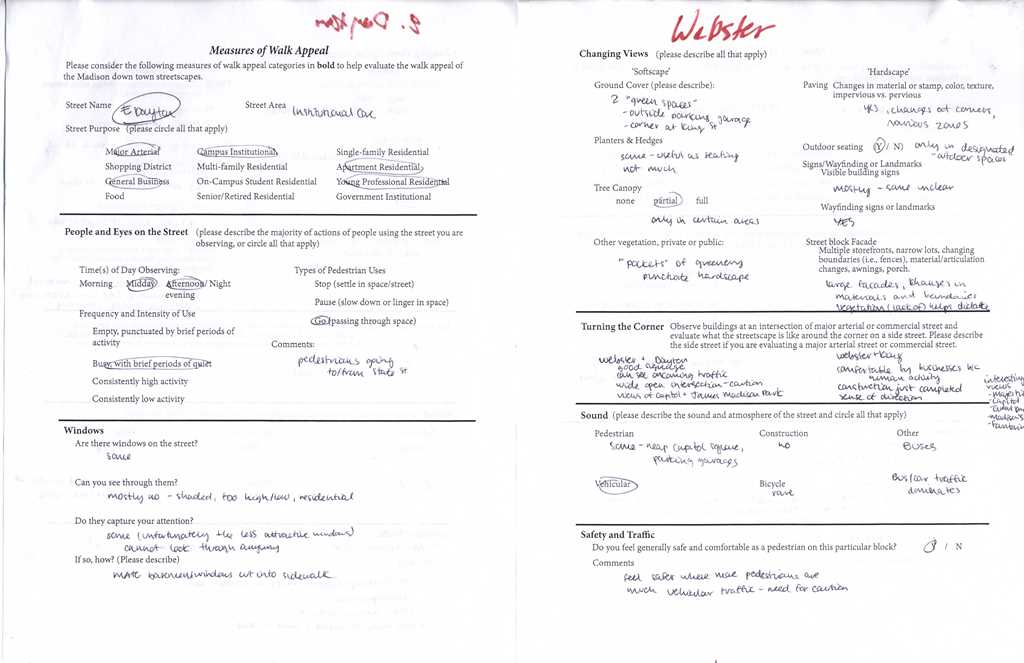

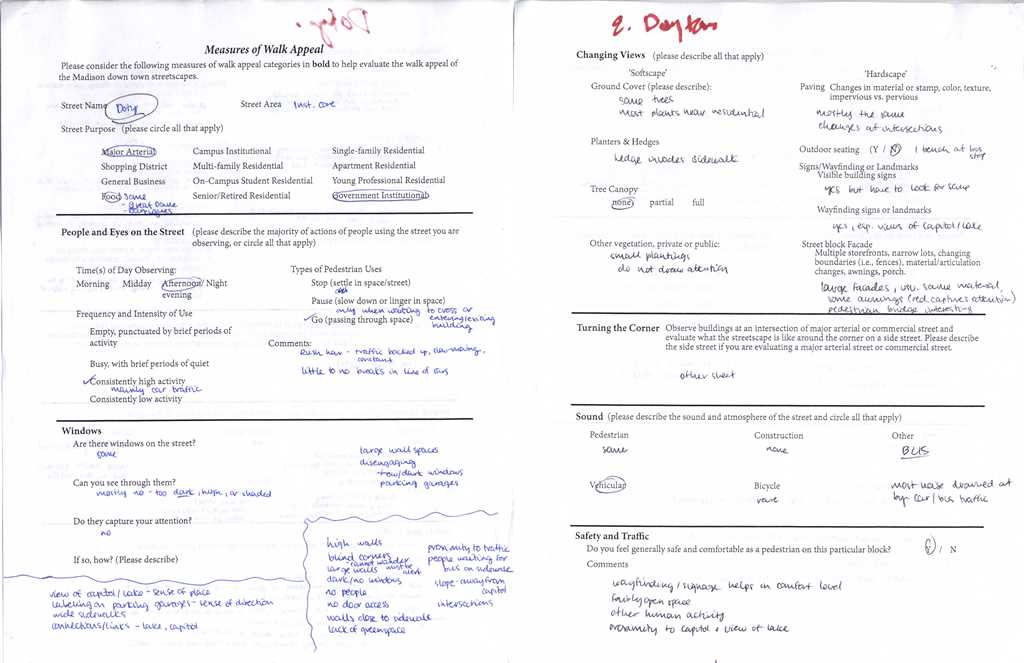

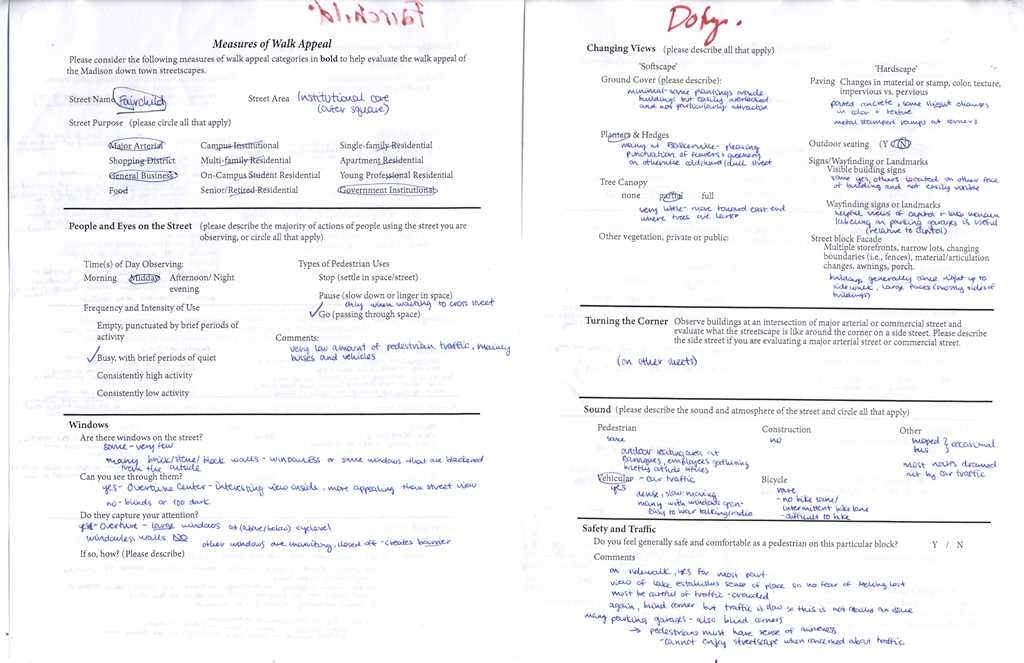

The data sheet, developed by Terri Hong and me (with the work of Florida planner and architect Steve Mouzon as the theoretical underpinning), is an iterative one. As we work with more classes and more students this upcoming academic year, we will improve upon this series of metrics. Students’ completed data sheets are below:

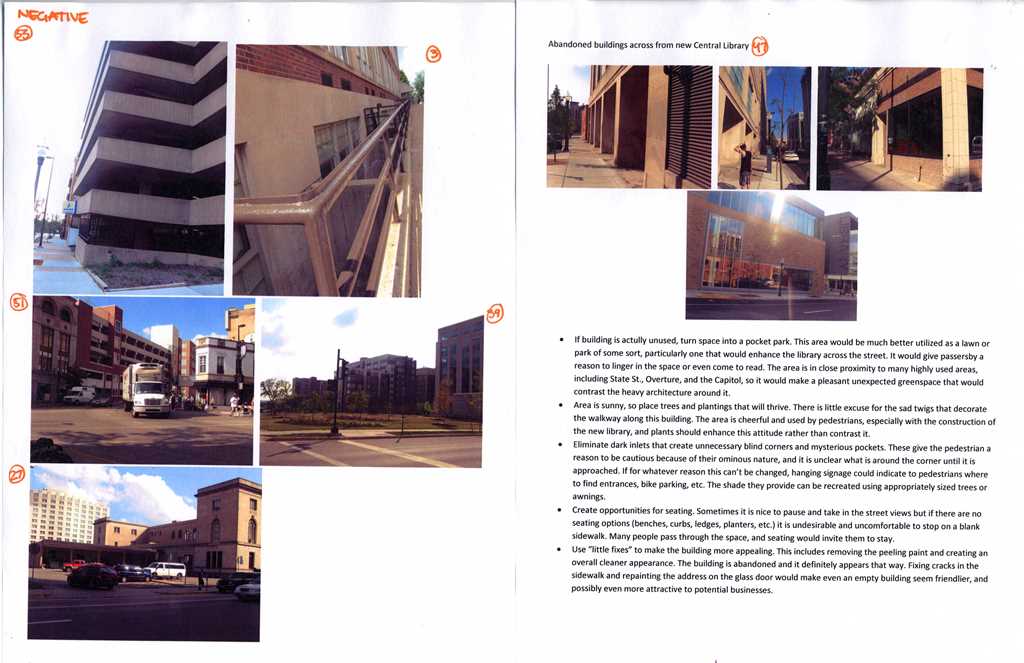

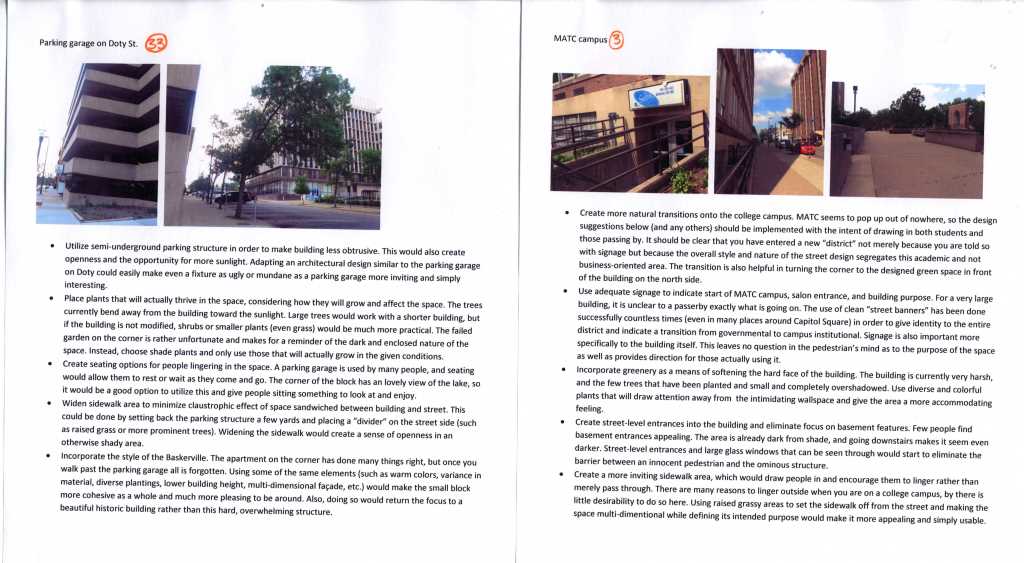

All three students used pictures as well as words to help describe what they experienced walking on Madison’s Outer Loop. Below are annotated photos of what they viewed as the biggest trouble spots.

The Conclusions

The three landscape architecture students identified many of the same problem areas, and the Outer Loop’s walk appeal issues came up again and again. To summarize the students’ assessment of the negative and positive aspects of the Outer Loop’s walk appeal:

Lack of purpose – students mentioned that in contrast to the new Central Library (pictured below), many buildings and blocks of the Outer Loop have no clear purpose and present little of interest to the pedestrian.

Poor wayfinding (i.e., signs only for drivers) – On a similar note, students astutely observed that signage on the Outer Loop is adequate for drivers but nearly nonexistent for pedestrians. In contrast to the Capitol Square and State Street, where signage and wayfinding improvements have been funded by the Business Improvement District, the Outer Loop (only one block away!) presents few clues for the pedestrian trying to find his or her destination.

Parking garages – Students noted the poor walking environment created by the parking garages on Fairchild and Doty streets while lauding the streetscape at the Webster Street garage (pictured below). The Webster garage reminds us that just because a particular land use is not conducive to pedestrians does not mean that its interaction with them at the street level must, therefore, be antagonistic.

Lack of seating – Students observed that what limited public seating does exist on the Outer Loop is not very inviting to pedestrians and often seems private rather than public. One student also singled out seating for bus stops, which can have inadequate (or no) sheltered seating.

Better transitions between roads and sidewalks – most of the sidewalks on the Outer Loop, according to students, sit directly against traffic, with little or no buffer between the sidewalk and the street. This creates a poor environment for pedestrians, who may feel trapped between tall, monolithic buildings and fast-moving traffic. Students suggest livening up building walls with color and green features and a buffer strip between pedestrians and traffic.

Abandoned spaces – Run-down buildings are urban features certainly not unique to the Outer Loop, but their presence less than 200 feet from the Capitol Square warranted a mention from all students. They note that these buildings negatively impact the walking experience but that they also present great opportunities: one student suggested turning a building into a pocket park.

Next Steps

1000 Friends is currently exploring a partnership with the City of Madison to help city planners evaluate walk appeal citywide. New leadership in the city’s Department of Planning and Development is eager to address issues of walkability in public spaces, especially along main transportation corridors, as upgrades to the city’s transit and bicycle infrastructure and emphasis on infill redevelopment in those corridors proceed apace. What’s needed is an ongoing effort to make sure that public spaces and the interface between the public and private spheres are designed, built, and programmed with people in mind.